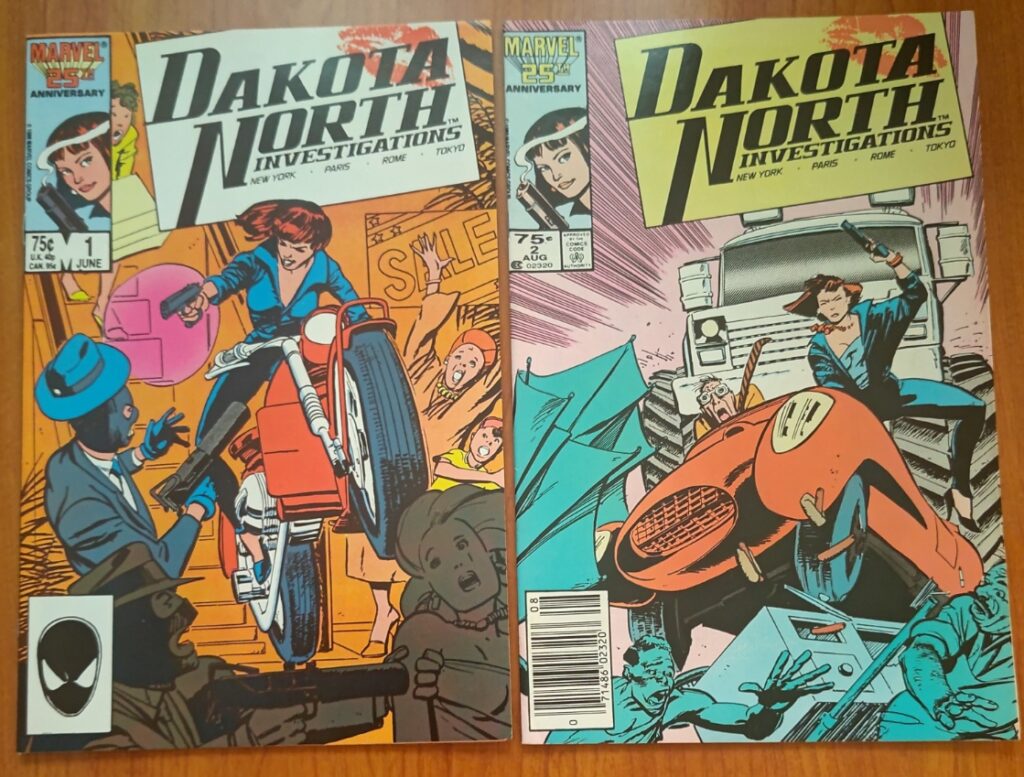

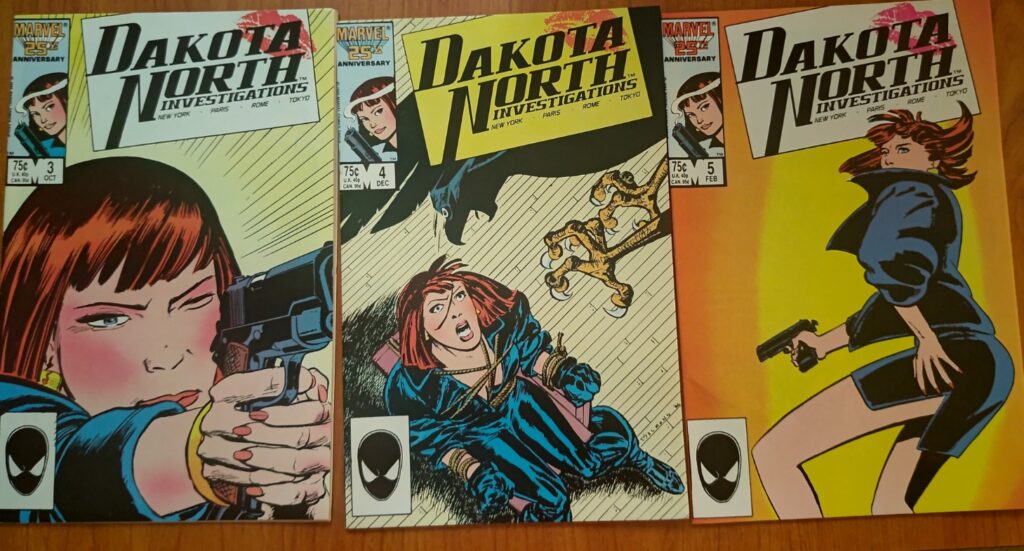

Unbagging Dakota North #1-5

Dakota North #1-5

Creators

| Writer | Martha Thomases |

| Artist | Tony Salmons |

| Colorist | Christie Scheele |

| Letterer | Jim Novak |

| Cover Artist | Tony Salmons |

| Editor | Larry Hama |

| Editor in Chief | Jim Shooter |

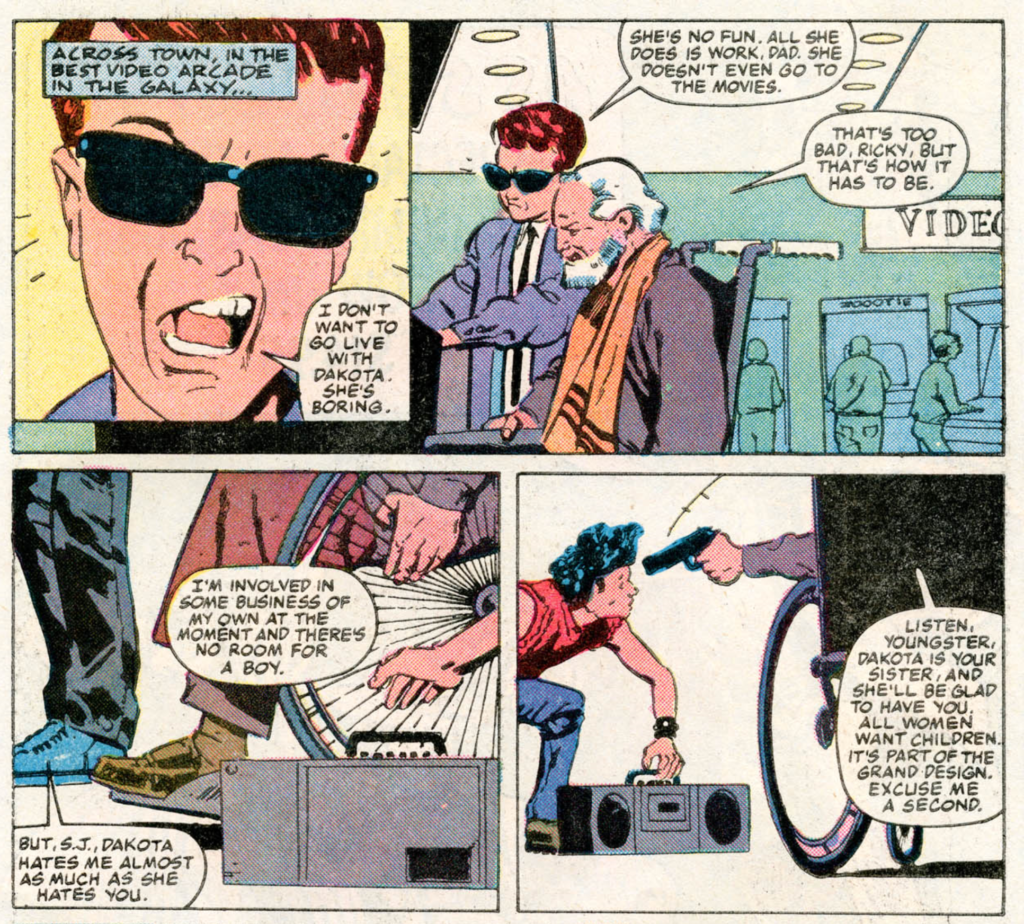

Do you hear me, Ricky? I don’t have room for a twelve-year-old boy.

This Unbagging is going to be a bit different from most, in that it’s focusing on a complete – albeit incomplete – series rather than a single issue, and also because, well, it’s going to be a bit less positive.

In general, while it doesn’t really align with my personality outside of these posts, I try to accentuate the positive when I write about comics here, given that the whole point of the site and the platform it’s part of is to share my love of comics.

Indeed, wanting to have positive things to say generally drives my choices when it comes to picking comics to write about.

Given that I recall liking the character in Daredevil (I had forgotten that she also appeared in Cage in the ’90s) and that I was always fascinated by the simple house ad for the series, I bought these issues hoping that it would be the case that I’d like them and might have sufficiently positive things to say about them to inspire a positive post.

Alas.

That said, it’s not a terrible comic, it’s just not good, and more than anything, it’s just…odd.

Part of that, I think, comes from the fact that it’s the first comic-writing work for Martha Thomases, whose background was in writing for magazines. That lack of background comes through in the ways in which the comic doesn’t really follow some of the standard tropes of comic storytelling of the time.

Obviously, breaking the mold and not being hidebound to traditions can be a good thing – and there was a lot of that happening at the time this series came out – but there are certain conventions that are conventions for a reason, particularly those that help give a narrative some kind of coherence.

And that’s actually why I decided to write a post about this short-lived series, as it relates to something I mentioned in my last Unbagging post:

There are also copious amounts of expository dialogue, which is both a strength and a weakness of comics of this era, whether they were written by Claremont or not.

The strength of it is obvious: someone who was as unfamiliar with the X-Men as I had been a few years prior to this issue could have picked it up and quickly gotten the gist of what’s going on, getting some understanding of who Wolverine is and how his powers work, with the same being true for Katie. You might not even know that the Power Pack exists, but thanks to the – rather clunky – explanations provided, you’d know that it’s a team that consists of Katie and her siblings, and you’d know that she uses the code name Energizer, and that she has the power to disintegrate objects, absorb their energy, and then discharge that energy as destructive energy blasts.

Basically, this comic doesn’t have that. That’s not to say there is no exposition, but it’s inconsistent, and is often done in a way that feels even less natural than a Claremontian infodump.

And it’s a problem, not only for a new reader who might have just randomly picked up issue number two, but also for people who have been there from the start, because we never get any real explanation of what’s going on or who anyone is.

We get little bits of background information here and there, but nothing like an “origin story,” or detailed backstories for Dakota or any of the people around her.

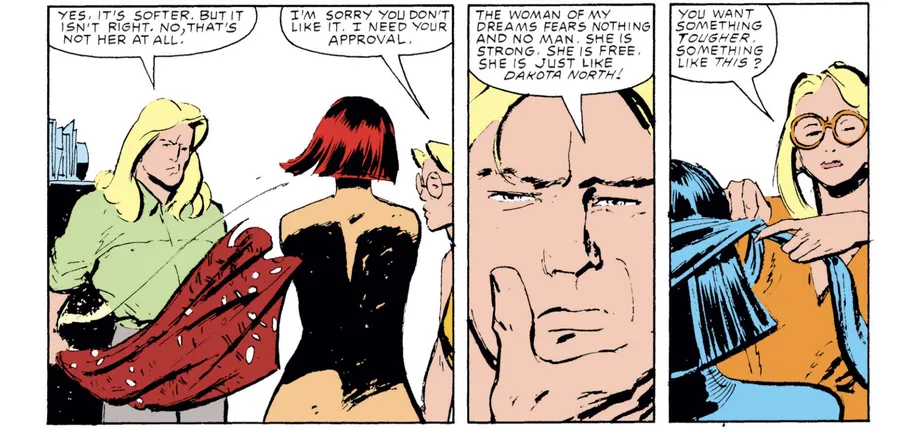

Honestly, we don’t even know what she does. The logo on the cover says “Investigations,” but it seems like she’s really more of a private security service, as her first – and pretty much only, but more on that in a bit – job is to be a bodyguard to a fashion designer, though she does do some investigating to try to find out who’s behind the attempts on his life.

That’s actually one of the more interesting aspects of the book – it turns out that the client would, decades later, be a deep cut character on a Disney+ series.

Unlike his counterpart on She-Hulk: Attorney at Law, here, Luke Jacobson is a white – and, improbably, straight – guy, and is not in the business of designing fashion for the superhuman crowd.

That first meeting with a client kind of helps to set the odd tone and pace of the book.

Basically, stuff just happens. Constantly. And not just in the foreground, either. The whole approach to making the comic reminds me of the filmmaking style of Harold Zoid.

In that client meeting, Dakota takes her motorcycle up to a studio in an elevator, is immediately mistaken for a model and without being able to object, forced to change clothes, handed a make-up kit and told that she must improve her looks before meeting with Luke, realizes that the make-up kit she’s been handed is far too heavy, so she tosses it out the window just as it explodes.

From there we meet Dakota’s father, S.J., and her twelve-year-old brother, Ricky. The wheelchair-bound S.J. wants Ricky to stay with Dakota. Ricky doesn’t want to and deems it likely that Dakota won’t want him to but acquiesces when S.J. offers him $200 a week.

Oh, also, the woman who hired Dakota to protect Luke is the head of the corporation that bought Luke’s design firm, and she’s also paying the people who are out to kill Luke. For reasons?

Luke’s boss, Cleo Vanderlip, is the primary, behind-the-scenes antagonist. It’s never quite clear what she wants, but she seems to have some kind of personal vendetta against S.J., and, by extension, Dakota.

Hating Dakota puts Cleo in the minority, as most everyone else – except Ricky and possibly even S.J. – seems to love her, especially Amos, the random NYPD detective who just shows up at her place every so often like a lovestruck puppy, one who keeps getting encouraging words from Dakota’s assistant, Mad Dog.

The issue ends with Dakota being told by Mad Dog – who is twinning with Ricky for some reason – that S.J. called to tell Dakota that her husband is in town and wants to meet her for dinner. Everyone seems surprised to learn that Dakota is married.

The next issue opens with Dakota and Ricky heading to the restaurant to meet her mysterious husband, while some guy hiding in the shadows is engaging in a soliloquy about how much he’s in love with Dakota but doesn’t want her to take the job she’s about to be offered and then makes a half-hearted attempt at shooting her with a crossbow.

He manages to make his getaway and Dakota and Ricky head inside where we learn that the line about a husband was just a ruse on the part of her father to get Dakota to come to the restaurant, though he notes that the friend who’s there with him could be Dakota’s husband, if she’s willing, though that’s not why he wanted her to come to the restaurant.

Also, the guy who tried to shoot her with a crossbow shows up and asks her to dance and she agrees even though she realizes he’s the guy who tried to shoot her with a crossbow, and then he leaves after stealing a non-consensual kiss.

Pretty much the rest of what happens in the series flows from here. The old friend of S.J. is a retired military officer who’s working on a book about his time in the military. While Dakota and S.J. are arguing, he plays poker with Ricky and keeps losing, ultimately owing more than he has on him, and opting to give Ricky a gold pen as collateral until he can get more cash.

Except he lost on purpose, and the pen is filled with a sample of some kind of nerve gas, and like I said, things just happen in this book.

Anyway, he gave it to Ricky because he assumed that it would be safer with him, because reasons. Mostly that no one would think that a kid has a gold pen filled with deadly nerve gas, which, I mean, I guess?

However, Cleo does think that, and she wants the nerve gas. To get it, she enlists a sixteen-year-old model in her employ to woo Ricky so that she can grab his pen (not a euphemism).

She is successful in wooing Ricky, and tricks him into running away with her, first to Paris, and then on to the Orient Express.

However, Ricky, without really trying, is able to successfully woo her, and ultimately she decides that she has no interest in completing her mission.

Ricky ends up getting caught anyway, and Daisy – the young honeypot sent to trap Ricky – is forced to fly back to New York to face the music for failing to deliver Ricky and the pen to their destination.

All of this happens while Dakota is off in pursuit of Ricky and his golden pen. Along the way, we’re treated to a cavalcade of European and eventually Arabic stereotypes who flail their arms around in the background and occasionally throw a pie or two (metaphorically).

Also, Amos follows Dakota to Europe, even though taking his unused vacation time lands him in hot water with his boss and he’s not really bringing anything to the table that the considerably more capable Dakota doesn’t already have.

Oh, and Cleo, who has never actually met Amos, but knows him because she spies on Dakota, shows up just as he’s getting ready to leave and offers to take care of his cat while he’s in Europe. I mean, who hasn’t had the CEO of a powerful corporation randomly show up and offer to catsit, right?

At the end of the whole adventure, after Dakota learns that Cleo has been behind everything, there’s a sort of confrontation between Cleo and S.J. that makes it clear that they have something of a love/hate relationship.

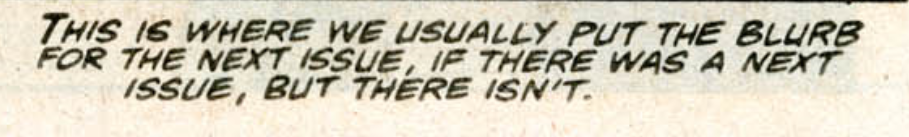

But that’s all we learn, as it’s the end of the series.

From what I’ve read, the book sold reasonably well, and no real explanation was given to the creators as to why it was cancelled. The speculation is that Jim Shooter, the Editor-in-Chief at the time, decided to give it the axe because he had to cancel something and he was too committed to the low-selling books of the “New Universe,” which had been his baby, to cut any of them.

However, I’m not the only person who noticed the room for improvement and lack of coherence in the book, as can be seen in this excerpt from a letter from reader Matthew J. Domnarski printed in the final issue:

Reader Alexander Bledsoe also hits upon something that stood out to me. Dakota presents as being fairly affluent and successful – she has international offices, after all, and dresses in expensive leather finery – but there are also the periodic mentions of not being able to pay her bills, being desperate for a paying customer, and keeping the creditors at bay.

Ultimately, it just seems like the book doesn’t know what it wants to be. Is it modern noir with a focus on style and fashion? An international thriller? A spoof? It’s never clear. There’s too much goofiness for it to be taken seriously, but it’s not quite goofy enough to be fun. Or rather, it’s goofy in a way that’s kind of annoying and baffling rather than entertaining.

Because honestly, I should be able to enjoy a late-Bronze-Age book that has levels of wackiness that would put many Silver Age books to shame. At one point, a sheik dispatches his trained falcon to kill Dakota while she’s tied to a chair, and she manages to maneuver in such a way as to get the raptor’s talons to cut her ropes; I should be all about this.

But the over-the-top ridiculousness that should be fun is undercut by the WTFery of a lot of the dialogue.

I just think the book could have used more focus and would have been better if it had settled on a genre, or even just a better blend of genres, but it ultimately has too many things going on at once – Fashion! Intrique! Humor! Romance! Social Commentary! Action! Suspense! – and too poorly at that to really find its groove.

And then there’s the other problem I mentioned already – we just don’t get enough explanation about anything. Too many things just happen for no apparent reason, and, again, we barely know anything about the characters we’re supposed to care about. I said there are weaknesses to the kind of storytelling that was prevalent in this era, but I also said there were strengths.

The lack/poor delivery of exposition is a particular problem for a book that only came out every two months, but even as someone who sat down and read all five books in one sitting, it was hard to keep track of what had happened in the previous. (Some/much of that can be chalked up to my aging brain.)

We also didn’t really get enough insight into what characters were thinking. I still don’t know what Cleo was up to, and there was no indication until she finally came out and said it that Daisy had undergone a change of heart and had fallen for the charms of the charmless boy.

On the other hand, we constantly got insights into the inner lives of tertiary characters, like Luke’s assistant, Anna, who was also secretly helping Cleo with her evil schemes (whatever those were). All throughout the series we have to stop and check in on how she’s torn between her duty to Cleo and her secret love for Luke. (She keeps it a secret, in part, because she believes it to be unrequited – and rightly so, in her mind, because she has self-esteem issues – but also because she thinks Cleo would make fun of her for being foolish enough to think that anyone could love her. And also because Luke keeps going on about being in love with Dakota, who isn’t the least bit interested in him.)

The biggest problem with the series, though, is probably my own preconceived notions of what it was going to be like based almost entirely on a simple house ad.

I was expecting something more like Modesty Blaise, or at least like some of the sexy and stylish private investigator TV shows of the era, and I had this idea in my head that Dakota was a fashion model turned P.I.

So a lot of my disappointment is on me. But not all of it, because the book really was kind of a mess.

As for the art, overall, it had potential – Salmons, at times, reminded me a bit of Butch Guice – but it was pretty messy and oversimplified, and the storytelling flow was often non-existent, adding to the overall sense of confusion.

I recall reading an interview in which someone mentioned that there was a time that the printing company Mavel worked with switched from using metal to plastic printing plates. I don’t recall who the interview was with, or where I read it, nor can I find any information to corroborate my memory or confirm when they may have been in use.

However, if my memory is correct, I suspect that it would have been around this time period, as it would explain a lot of the issues not only with the art in this series but also in other comics from Marvel at the time. There’s a blurriness too it, with too much spread from the black and a dullness to the colors.

With that in mind, I cut Salmons a lot of slack here, particularly given that he was a relative newcomer. He went on to improve in other books that featured his work (though in those cases he might have also been helped out by better printing).

I wouldn’t be so disappointed in this book if I didn’t think it had potential. I wanted to like it, and with some changes, I actually might have.

Maybe it would have reached its potential if it had gone on longer, but we’ll never know, and we can only judge what is, not what might have been.

There could be room for a modern revival of Dakota. After all, there’s a lot of focus on fashion with the whole Hellfire Gala thing, and one of her clients is a part of the MCU now. So who knows? Maybe there’s still a chance for Dakota to live up to her potential with substance as well as style.

Born and raised in the sparsely populated Upper Peninsula of Michigan, Jon Maki developed an enduring love for comics at an early age.